I wanted to declare something like “most writers pursue their craft as a means of self expression,” but I realized even the phrase “self expression” connotes interiority and poetics to the exclusion of other purposes. So let me establish, before anything else: that’s silly. Journalism, academia, drama, fiction, poetry, and automatic stream of consciousness diaries are all engaging the ideas and experiences of the author/s selves through literary mediums. They use different devices to different ends, but any writer who claims to like writing is relieving a tension which is, to some degree, personal.

I long thought of raw drafting as the only expressive part of the process. Like a lot of fledgling writers, I mistook the act of drafting as essentially the same thing as writing. As a teenager, I regarded my over-sharing, unfiltered LiveJournal (and MySpace, Facebook, and Tumblr) entries as catharsis, and resisted accepting any feedback that might corrupt their pure purpose of making me feel better. Criticism didn’t bruise my ego, it bounced off of it, because anything but immediate enthusiasm for my drafts was just yet another person misunderstanding my efforts.

Ridiculous as it all seems now, I’m glad my adolescent art had such a wide stubborn streak down the middle. A few influential teachers along the way knew to ask me “so what?” and made me explain my impulses and preciousness again and again or let them go altogether. At eighteen I observed a lecture and workshop with a monk who made intricate mandalas in sand and then threw them into a river when they were finished. I made peace with a few crashed hard drives and lost notebooks. I came to see drafting as gathering material, not even assembling it yet, much less polishing. All of this allowed me to shape and mature my process and my voice into something more resilient than stubborn, and more fluid than nebulous. Rejection does not make me feel like a misunderstood art martyr anymore, but it does make me ask where along the way my messages got lost, and to ask “so what?” until they actually do what I meant for them to do.

For the next decade or so, it seemed that revision, rewriting, and publication were about cleaning up nicely. Drafting a piece was the feral self and making it readable and publishable was socializing it, a necessary trade off, so I thought, of taming base antisocial impulses in exchange for more effective communication. But recently I was reading a behavioral therapy essay, “Grieving and Complex PTSD: Fear as Death of Safety,” and a great deal of what the author, Pete Walker, had to say about effective therapy reminded me of tips I’ve seen about creative practice. It also gave me an unexpected insight into what I was still missing in my attitudes.

Walker writes that in treatment for C-PTSD, venting through speech or writing is most useful when it engages both self expression as well as analytical search for the right language. “Verbal ventilation is only effective,” he says, “when it is liberated from the [inner] critic’s control. In early recovery, verbal ventilation can easily shift into verbal self flagellation.” Translated into writing advice, this is more or less “shush your inner critic and keep going,” the very spirit of NaNoWriMo and other tools to overcome the initial perfectionist fear of starting.

But Walker clarifies, “It is important to differentiate verbal ventilation from dissociative flights of fantasy or obsessive bouts of unproductive worrying.” And here I recognized that first, critical lesson that feeling strongly is not the same thing as a good idea, that a frantic and inspired draft is not the same thing as communicating effectively.

For those terrified of critique altogether, who come away from groups and workshops crestfallen and discouraged from ever writing again, Walker acknowledges that “authentic and vulnerable sharing can be extremely triggering, and can easily flash the survivor back to experiences of being attacked, shamed or abandoned.” There’s a ton of great advice out there about how to give criticism constructively, without attacking the writer, but it may be productive as the one getting the day’s critique to reaffirm reality, and know you can’t get grounded or fired or excommunicated from writing just because you didn’t nail the ending or the extended metaphor this time.

Finally, Walker describes the best case scenario. “Verbal ventilation, at its most potent, is the therapeutic process of bringing left brain cognition to intense right brain emotional activation.” Reading this, something clicked for me about how I understood self expression and my writing process. Editing was not in opposition to catharsis; it was necessary to complete the release. Do not view criticism as something you need to suck up and receive like a blow. The cycle of idea, draft, feedback, revision, rewriting, and even publishing was a unified whole; not acts of civilizing self expression, but a process of integrity with that self expression, and more effectively cathartic for it.

-Julian K. Jarboe, 2018 WROB Fellow

Full disclosure: This blog post should’ve been up

Full disclosure: This blog post should’ve been up

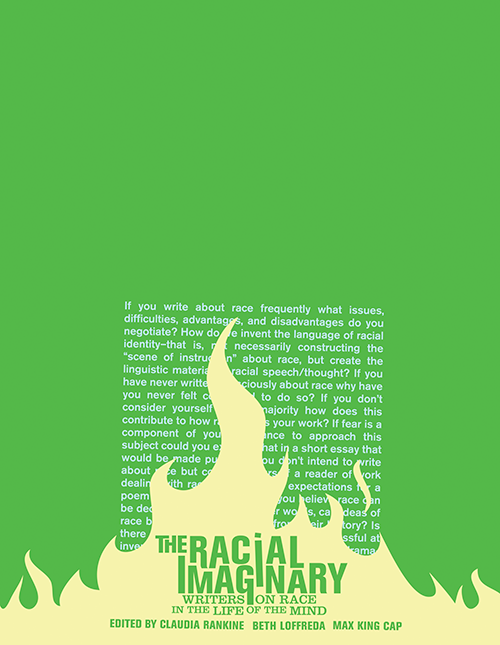

In Claudia Rankine and Beth Loffreda’s excellent anthology The Racial Imaginary: Writers on Race in the Life of the Mind, they write in their introduction that “our imaginations are creatures as limited as we ourselves are. They are not some special, uninfiltrated realm that transcends the messy realities of our lives and minds. To think of creativity in terms of transcendence is itself specific and partial–a lovely dream perhaps, but an inhuman one.” This is not a prohibition against writing “the other.” It’s a call to look at ourselves and our work and the work we value with our eyes open.

In Claudia Rankine and Beth Loffreda’s excellent anthology The Racial Imaginary: Writers on Race in the Life of the Mind, they write in their introduction that “our imaginations are creatures as limited as we ourselves are. They are not some special, uninfiltrated realm that transcends the messy realities of our lives and minds. To think of creativity in terms of transcendence is itself specific and partial–a lovely dream perhaps, but an inhuman one.” This is not a prohibition against writing “the other.” It’s a call to look at ourselves and our work and the work we value with our eyes open.