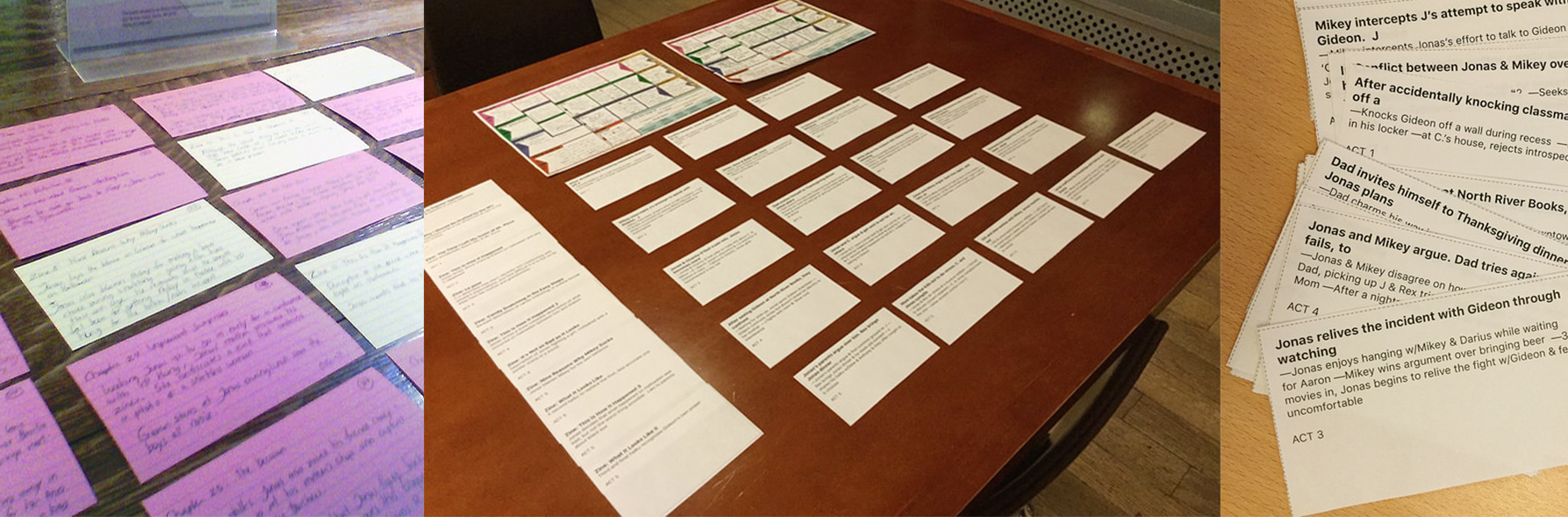

I make my way on the orange line to the State Street train station in hopes of heading to my sacred writing space. I enter the quiet room and I immerse myself into my work in hopes of getting further along in my writing project. It sounds like the perfect set up yet when the moment arrives I find myself stopped. For awhile I thought I was experiencing writer’s block, but it hasn’t been about a lack of things to write, I’ve been trying to determine the right thing to write. Many people would call this “THE CRITIC.” The inner voice that yells “your writing is terrible” before you even get the words out. The internal editor that stops you before you even utter a word. The small voice encouraging you to put off writing until a “genius” or “beautiful” passage is created.

This constant state of paralysis while writing has made me think of my childhood. I used to read free books that my family got from shelters and donation bins. We were living beneath the poverty line so, interestingly enough, I found myself with a ton of classics portraying worlds incredibly far from my own. I was reading “David Copperfield” or “Little Women” and falling in love with books more and more each day. I was so in love with them I tried to make my own. I wrote without worry about whether my plot made sense, or if my characters were developed, or if my line breaks were in the right spot. Somehow as I got more information about literature and the world of writing, my ability to be free while writing dwindled away.

One of the reasons I’ve always loved creating, whether it was a book, a dance or my own theater play with my siblings as actors, was because it was free. And not free in the commercial sense of the word, free in the sense that what I created was mine. It wasn’t under the influence of my future inner critic, the world of publishing or a commissioner. I could create to express, explore and connect.

It’s probably impossible for me to recreate the type of freedom I had as a child, yet I am challenging myself to write whatever is in my head. I am challenging myself to let my thoughts avalanche onto a page and make absolutely no sense. I am abandoning the “project” or the “mission.” I am challenging myself to fall in love with the joy of creating something. I am allowing myself to revel in that space, if only for a moment. Until my inner critic learns what’s going on and tells me to stop, so I can start the process all over again.

-Tatiana M.R. Johnson, 2018 WROB Gish Jen Fellow

In second person narration, when you stands in for I—that is, when readers or secondary characters aren’t being addressed—we understand that our protagonist is both narrator and narratee; we are privy to a telling or retelling of a story handed off to, and received by, a psyche fractured by the passage of time and/ or an altered understanding of events. This fracture, I would argue, more similarly reflects how we experience the world: Subject meets stimuli and interprets then reinterprets to create narrative; we tell ourselves the story of what is happening to us as it is happening, and many times afterward. Similarly, our second person protagonist exists both within the story’s events and in the consciousness that orders and reorders the events to create meaning.

In second person narration, when you stands in for I—that is, when readers or secondary characters aren’t being addressed—we understand that our protagonist is both narrator and narratee; we are privy to a telling or retelling of a story handed off to, and received by, a psyche fractured by the passage of time and/ or an altered understanding of events. This fracture, I would argue, more similarly reflects how we experience the world: Subject meets stimuli and interprets then reinterprets to create narrative; we tell ourselves the story of what is happening to us as it is happening, and many times afterward. Similarly, our second person protagonist exists both within the story’s events and in the consciousness that orders and reorders the events to create meaning. This fall, WROB member Camille DeAngelis published Life Without Envy: Ego Management for Creative People. This is not the sort of book I normally read but knowing Camille, I dove in. Camille spends most of the book focused on the dangers of comparison: because that other person published/sold/wrote/won means I should.

This fall, WROB member Camille DeAngelis published Life Without Envy: Ego Management for Creative People. This is not the sort of book I normally read but knowing Camille, I dove in. Camille spends most of the book focused on the dangers of comparison: because that other person published/sold/wrote/won means I should. Awards for the Emerging Writers Fellowship Program are based on the quality of a submitted writing sample, a project description, a CV or resume, and a statement of need. The Fellowships are open to writers working in any genre or form. Fellows must be committed to: using the Room on a regular basis throughout the 12-month period, writing a minimum of 6 blog posts for our website, and assisting with WROB readings and events.

Awards for the Emerging Writers Fellowship Program are based on the quality of a submitted writing sample, a project description, a CV or resume, and a statement of need. The Fellowships are open to writers working in any genre or form. Fellows must be committed to: using the Room on a regular basis throughout the 12-month period, writing a minimum of 6 blog posts for our website, and assisting with WROB readings and events.