Why review books? What’s the point? To what useful end is one reader’s take on someone else’s art beyond her own delight, neutrality, or regret for having engaged?

One might return a question: why review ANYTHING? Opinions, everybody’s got ‘em, right? So.

So. Memory . . .

In the 80’s and 90’s, my brother and I rocked the summer reading club scene at both libraries we frequented. That’s right, we competed in reading against other, unseen children, jockeying for the coveted position of Most Books Read. My brother and I weren’t opponents –these races were more like track and field where one challenges his history: his past record, his younger self.

At summer’s end, we’d conclude with fistfuls of Pizza Hut personal pan pizza coupons and, for me at least, zero memory of what I’d read beyond titles listed on a colorful sheet of paper, forgotten ever more deeply as summer’s expansiveness compressed into rigidly structured fall.

Learning . . .

My brother has four years on me and, other than a few shared Spider-Man and Garfield comics, a Robotech novel or two, we didn’t have many cross-over reading interests. Despite this, I hold dear titles that I myself never read, such as Dear Mr. Henshaw by Beverly Cleary and From the Mixed-Up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler by E.L. Konigsburg. The book reports he wrote for school were as amazing and sophisticated sounding to me as what he was reading. I felt eager to compose my own reports–craft construction paper covers, hand-letter the titles, staple along the edges, and present proudly to a teacher one neat bundle.

Sadly, my schooling was not his; I didn’t score any grade school teachers who assigned book reports. By the time I was invited to commune with literature, I was in high school where the culture was less about connecting with written words and more about strategizing to achieve A’s. I loved and identified with novels and poetry but still removed myself from an Honor’s English class because I didn’t care to compete and had a growing dislike of lit-tret-ture.

Memory . . .

I have a micro-myth, goes like this: I was reading The Hero and the Crown by Robin McKinley, so into it, awww YEAH! This book is GREAT, this book is fantastic. Nearing the final pages, situations started to feel a tad . . . familiar, and then really familiar, and then. Oh, no. I’ve already read this book. I KNOW HOW IT ENDS. 🙁 🙁 🙁

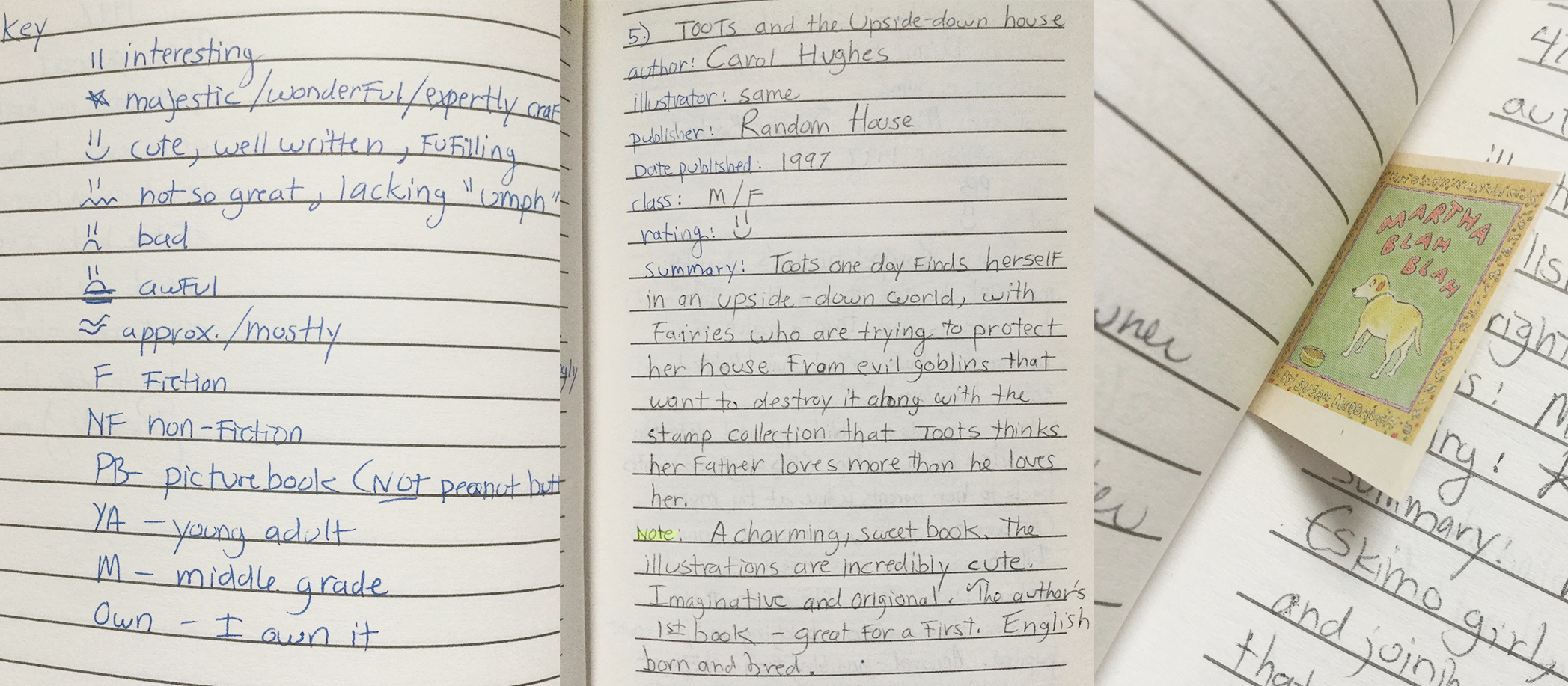

Thus, I started keeping reading journals in high school, hardbound books usually gifted to me by my brother. Curiously, the practice failed to save me from accidentally reading The Hero and the Crown a third time (consistent, that kid), but it did help cement the awareness that I shouldn’t attempt to keep everything in my head. I quickly devised my own rating system consisting of smiley faces and frown-y faces and wavy lines. The journals doubled as a study of the writing field and I recorded authors, illustrators, publishing houses and imprints, and award-winners.

Learning . . .

The result of eight-straight-years of writing instruction in high school and college is that I’ve learned systems and strategies for analyzing the narrative arts. I peek behind and betwixt typeset words for clues about work and writer both. The why of it: to read deeper, write better, understand our lives and our world(s) in the moment of the narrative, and then again and again with each unique book-poem-play, even as those books-poems-(comics!)-plays sometimes meld together into a mash of ideas. They soak through, get integrated and because of my . . .

. . . Memory, or lack thereof, I review books and STILL forget them. Alternately, there are poems I’ve heard just once that stick with me. It’s unpredictable. It’s delicious.

When the Internet arrived (for me) in college, so too arrived ingenious applications like Goodreads. At current count, I’ve posted approximately 400 reviews. Sure, one such review (for Microcrafts: Tiny Treasures to Make and Share by Margaret McGuire) is a simple exclamation: “So cute! So tiny!” but that’s an honest reaction, yeah? It’s me talking back to the writer/artist as much as my six-paragraph rant about Steven Pinker’s The Blank Slate: The Modern Denial of Human Nature. Sometimes other Goodreads users click the thumbs-up button, declaring their affinity with my analysis and I get a nice energy boost.

Aaaand learning . . .

As my world has expanded via the 0’s and 1’s, I’ve grown more careful with the reviews I pen. Words on a website are not the same as ideas on paper, bound by twin case covers, sitting on my shelf at home. I’m aware that the authors I watch from afar may one day be close-up peers. Taking care is a must. After all, care is the reason I’ve engaged, why I’m talking back to a writer or artist, explaining: this is how you reached me. See? Here’s how I’ve changed.

-Phoebe Sinclair, 2018 WROB Ivan Gold Fellow

Full disclosure: This blog post should’ve been up

Full disclosure: This blog post should’ve been up

Last month I was invited to take part in Together We Rise, a Counter-Inaugural Celebration of Resistance. As an artist who has been subjected to persecution, illegal imprisonment, torture and exile, I was asked to talk about the role of the artist in times of oppression. Here is the testimony I gave at the Strand Theatre on the evening of January 19th, surrounded by a community of dreamers and fighters:

Last month I was invited to take part in Together We Rise, a Counter-Inaugural Celebration of Resistance. As an artist who has been subjected to persecution, illegal imprisonment, torture and exile, I was asked to talk about the role of the artist in times of oppression. Here is the testimony I gave at the Strand Theatre on the evening of January 19th, surrounded by a community of dreamers and fighters: Awards for the Emerging Writers Fellowship Program are based on the quality of a submitted writing sample, a project description, a CV or resume, and a statement of need. The Fellowships are open to writers working in any genre or form. Fellows must be committed to: using the Room on a regular basis throughout the 12-month period, writing a minimum of 6 blog posts for our website, and assisting with WROB readings and events.

Awards for the Emerging Writers Fellowship Program are based on the quality of a submitted writing sample, a project description, a CV or resume, and a statement of need. The Fellowships are open to writers working in any genre or form. Fellows must be committed to: using the Room on a regular basis throughout the 12-month period, writing a minimum of 6 blog posts for our website, and assisting with WROB readings and events.