Several years ago I wrote a few short stories, one after another, that each had some kind of artist for a protagonist. They took various guises and encountered various fates, but when I stepped back and looked at them side by side, they were all about characters who gained a sense of agency and belonging through their work. Their art was transformative to their lives. I didn’t plan this, and it took me a long time to make the connection–I don’t think it’s a stretch–that while I was writing these stories, I had been working through the question of whether or not to pursue my MFA. I also didn’t observe, until much later, that I had written each and every one of these artists as male and white.

*

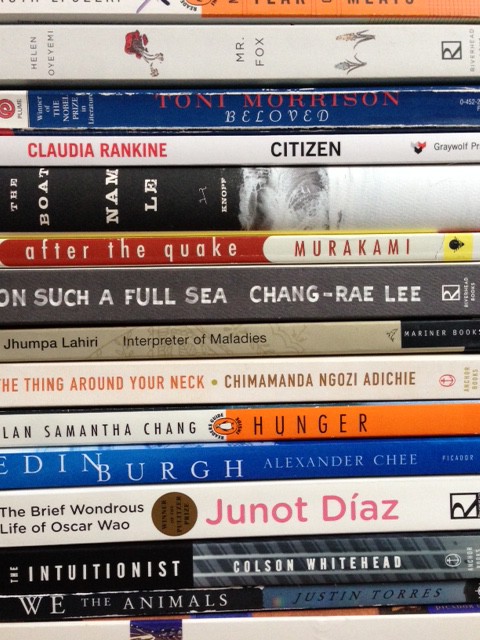

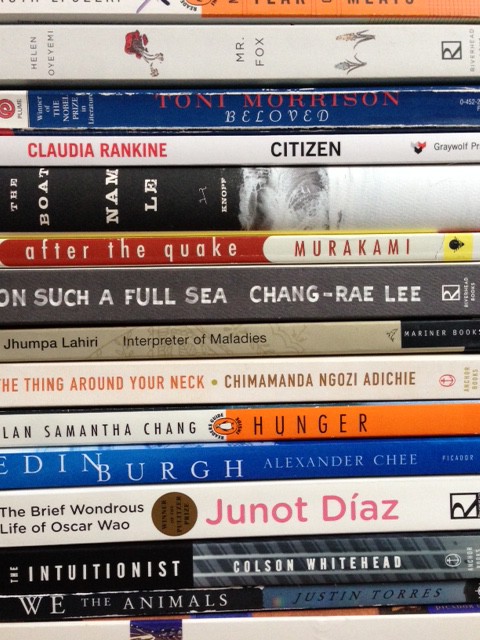

The New York Times recently published a recommended summer reading list, comprised solely of white authors. Some excellent thinkers and writers have already commented on this, more eloquently than I can (for example, see Roxane Gay’s article on NPR’s Code Switch: http://www.npr.org/sections/codeswitch/2015/05/28/410015276/theworstgroundhogsdaytimetotalkagainaboutdiversityinpublishing), so allow me simply to say that it’s only the latest occurrence that necessitates the ongoing conversation about diversity on our bookshelves, in MFA programs, and in the publishing world. You’ve probably read or at least heard of Junot Diaz’s widely discussed “MFA vs. POC” article in the New Yorker last year (http://www.newyorker.com/books/page-turner/mfa-vs-poc). You have probably seen the yearly VIDA counts (http://www.vidaweb.org), and heard that this commendable organization is making efforts to expand the count to look specifically at women of color, at LGBTQI writers, and writers with disabilities.

Critics of this conversation often ask why it should matter. Why, if it’s the work that matters, should the writer’s race matter (or: gender, sexuality, age, ethnicity, nationality, religion, able- bodiedness, and so on). As though academia and the publishing industry that influence what we read are perfectly merit-based, neutral systems. As though the work is somehow conjured from a neutral mind, or is about a neutral world that doesn’t exist. As though language is a neutral medium. It is not. Consider the definitions and connotations of the words fair and dark.

There are a couple of strands of discussion here, and while they are intimately entwined, they should be parsed out. There’s the question of representation–of who gets to publish, who is reviewed, who lands teaching positions, and whose books we read. Then there’s the question of our own identities, relative to our writing–what we’re expected to write and why, what topics and voices are “off-limits” to us (if any), and how, when we choose to cross boundaries, do we do it effectively.

There are a couple of strands of discussion here, and while they are intimately entwined, they should be parsed out. There’s the question of representation–of who gets to publish, who is reviewed, who lands teaching positions, and whose books we read. Then there’s the question of our own identities, relative to our writing–what we’re expected to write and why, what topics and voices are “off-limits” to us (if any), and how, when we choose to cross boundaries, do we do it effectively.

About the former: it’s not an attack on white writers to ask for more parity. No one is saying their books are undeserved accomplishments. Nor is it an attempt to shame any of us as readers and writers and teachers. Instead it’s a plea to the literary community to recognize how much more expansive their reading lives could be, if only they would pay attention. The (predominantly white and male) literary canon is canonical for a reason–it’s brilliant, beautiful work. But think how much more beauty is out there for us to find, if only we would be open to it. Why would we deny ourselves that? The great works by writers of color are out there, and being written, and will be written. You just aren’t seeing them championed in The New York Times. The exceptions to this are sadly just that: exceptions.

As for the latter: I understand, and feel, the desire to write across boundaries. Clearly I had no qualms writing one white male character after another. But the difference between my writer self from a few years ago and the writer self I am today is that I now believe I must first recognize where my own identity sits in this society, relative to my character’s identity. What baggage or preconceptions I bring to my pen. When I write a character, I am trying to bring that character to life in the reader’s mind; I am asking the reader to take a leap of faith with me and to translate a few marks of ink on paper into an understanding of an entire person. What a strange and tremendous act, and, given how powerful narratives are in how we form opinions about the world, what a tremendous responsibility.

We are none of us immune to bias–cultural or otherwise. Was it important to the stories, that all my artist characters were white males? Probably not. So then, what did it say about me, an Asian-American woman trying to figure out how to write fiction, and what did it say about our cultural landscape, that when I imagined those who produced valuable work, I never imagined someone who looked like me? I’m not claiming that it’s wrong for me to write white male artist characters–it might be appropriate for a particular story. I’m saying that seeing this pattern within my own work made it abundantly clear to me that something was going on, and that I should sit up and pay attention. Because if I didn’t even realize what I was doing, the white bias I was replicating, what other biases am I unwittingly reinforcing on the page? It is my responsibility, as someone who wants my words to be read, to be as aware as I can possibly be of what I’m doing with those words. By the same token, we should all sit up and pay attention if we look at the writers we keep reading and teaching, and they all belong to one particular demographic. Maybe you have some good reason for it, I don’t know. But maybe you’re closing yourself off from books that will knock you over silly, they’re so good.

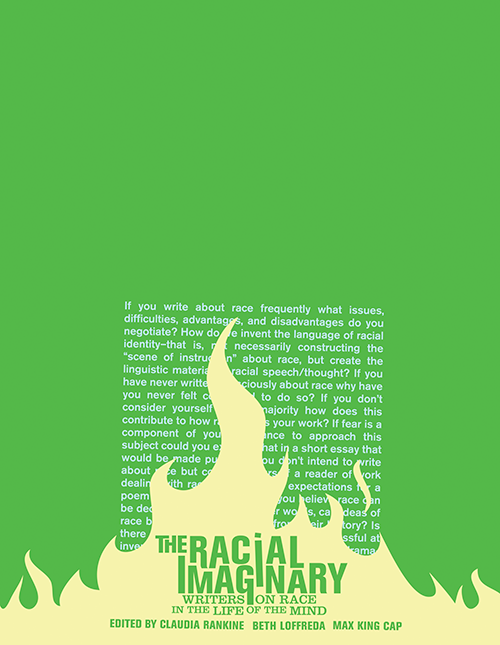

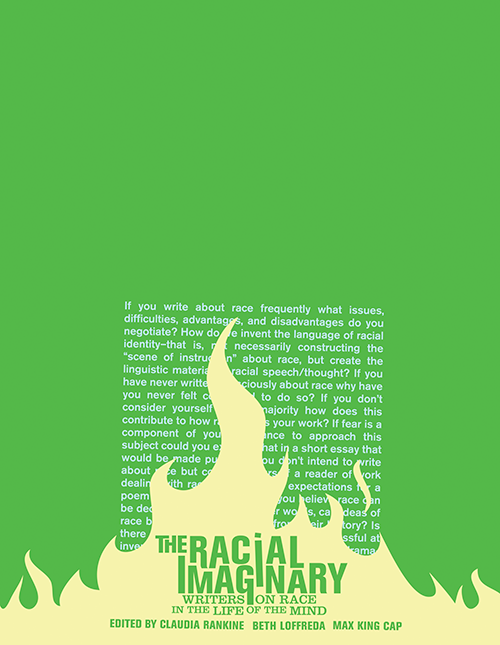

In Claudia Rankine and Beth Loffreda’s excellent anthology The Racial Imaginary: Writers on Race in the Life of the Mind, they write in their introduction that “our imaginations are creatures as limited as we ourselves are. They are not some special, uninfiltrated realm that transcends the messy realities of our lives and minds. To think of creativity in terms of transcendence is itself specific and partial–a lovely dream perhaps, but an inhuman one.” This is not a prohibition against writing “the other.” It’s a call to look at ourselves and our work and the work we value with our eyes open.

In Claudia Rankine and Beth Loffreda’s excellent anthology The Racial Imaginary: Writers on Race in the Life of the Mind, they write in their introduction that “our imaginations are creatures as limited as we ourselves are. They are not some special, uninfiltrated realm that transcends the messy realities of our lives and minds. To think of creativity in terms of transcendence is itself specific and partial–a lovely dream perhaps, but an inhuman one.” This is not a prohibition against writing “the other.” It’s a call to look at ourselves and our work and the work we value with our eyes open.

*

At my MFA program we’ve been having this conversation among the students, faculty, and administration over the past few years. To the great credit of my school, Warren Wilson, and the community it fosters, I have not personally experienced what Diaz describes from his own MFA experience as “an almost lunatical belief that race [is] no longer a major social force.” Instead, I have encountered student after student, of all backgrounds, who have told me that they want to have these conversations, they want to talk about the impact that identity politics have on their work and on our education. We are a community of students trying to figure out how we can process the world through our writing in thoughtful and meaningful ways. Last January, after an overwhelmingly positive response to a student-led discussion about the intersection of identity and craft, it took some time for me to sort out what felt like an internal ground shift. It was the first time I’d ever explicitly received the message that it can be okay, even welcome, to talk about these issues, and to think that my racialized, gendered self is also an artist self. That my artist self is also a racialized, gendered self. Even if it isn’t racialized as white, or gendered as male. It is a startling thing to understand what you have not been getting from the culture at large. Sometimes you don’t recognize it until you finally hear it.

*

Oftentimes, in these conversations that present hard questions, people want answers. Tell me what to do, so that I can be responsible and respectful. Do I take an affirmative action stance towards my own work? Towards my bookshelf? Do I use certain words and not others? What am I allowed to write? How do I not offend? The maddening thing is, I don’t think there are answers, not really. No singular answers, anyway. If this was an easy thing to address, if there was some checklist we could follow, we wouldn’t keep having the same conversations year after year, reading list after reading list. But I have become increasingly convinced that it is the active asking of questions that is most important, and the willingness to persist in the uneasy and uncomfortable. I have become increasingly convinced that it is only in the belief that this conversation matters at all that we can take small steps in our own work and in ourselves.

-Cynthia Gunadi, Ivan Gold Fiction Fellow

In Claudia Rankine and Beth Loffreda’s excellent anthology The Racial Imaginary: Writers on Race in the Life of the Mind, they write in their introduction that “our imaginations are creatures as limited as we ourselves are. They are not some special, uninfiltrated realm that transcends the messy realities of our lives and minds. To think of creativity in terms of transcendence is itself specific and partial–a lovely dream perhaps, but an inhuman one.” This is not a prohibition against writing “the other.” It’s a call to look at ourselves and our work and the work we value with our eyes open.

In Claudia Rankine and Beth Loffreda’s excellent anthology The Racial Imaginary: Writers on Race in the Life of the Mind, they write in their introduction that “our imaginations are creatures as limited as we ourselves are. They are not some special, uninfiltrated realm that transcends the messy realities of our lives and minds. To think of creativity in terms of transcendence is itself specific and partial–a lovely dream perhaps, but an inhuman one.” This is not a prohibition against writing “the other.” It’s a call to look at ourselves and our work and the work we value with our eyes open.