I recently attended a craft talk given by writer Pam Houston at the Vermont Studio Center. Houston focused on her process and what she calls “glimmers”—moments, images, conversations, or snippets of life that resonate with her as a writer. A keen observer of the world around her, she said these moments call out to her from everyday experiences. She collects these glimmers, jotting them down or saving them as visuals on her computer. What she does not do is try to unpack or over-think their significance. Not yet, anyway. Instead, Houston revisits these glimmers only when it’s time to write. Their significance to her only gets revealed on the page as she writes and organically makes connections. Her Contents May Have Shifted, is a collection of 144 of these glimmer vignettes brought together as a novel, a term she admitted to using loosely given its autobiographical nature and nonstandard narrative structure. It’s precisely how these moments come together and form a whole that offers insight into Houston’s distinct voice and glimmer process.

At the end of her talk, Houston had each of us write down three glimmers—one from the distant past, one from very recently, and one from anytime. It was an illuminating exercise. It then came time for volunteers to share those glimmers. Many were eager to share, offering explanations of a particular glimmer’s significance within the context of their lives. Some even deftly connected their glimmers to those of fellow attendees. It was marvelous. I hesitated. I felt a strong pull to my glimmers, but something was off. My first impulse was to preserve rather than unpack them and risk losing their luster. Feeling somewhat selfish, in that moment, I realized something about my own process. (I didn’t even know I had one.) It wasn’t my time to share these particular glimmers.

Since then I’ve been thinking a lot about how I (and writers in general) find inspiration or moments of connection and what we do with those moments. What comes after the connection, the initial spark, the glimmer? How do we nurture these ideas and protect them so they flourish on the page instead of losing their spark?

A glimmer itself, Houston’s talk resonated with the writers in attendance, myself included. Sometimes it’s a turn of phrase I hear, a striking visual, an entire forgotten story, or a strange reference in a historic text. I jot something down about that moment or idea quickly either in my journal or in an email to myself. I’m far from organized. I could easily create a central library for these ideas, but instead I send hundreds of emails to myself, a sort correspondence with my subconscious. My main intuitive goal—I’ve now realized— is to do a quick free-write of a few lines or even a very rough, kitchen-sink-type draft before I’ve had a time to self-examine, research, or process my experience of resonance. The stronger the pull towards the glimmer, the greater my need to preserve them in this way. Then, like Houston, I leave them to revisit later.

I’m not seeking written perfection from these ideas before I share. I just need a sense that I’ve birthed some unfiltered, uninhibited version of them, before my brain has caught up with me. Feedback, dialoguing with other writers, work-shopping, even my own internal unpacking, are all essential parts of my process. But the timing matters. I need to document that initial moment of resonance first, in however many words feels right.

Of course, my need to protect my initial idea often disappears once I begin the actual writing. I can’t predict where it leads. It’s like a game of telephone, where every time I revisit my initial topic of conversation, the dialogue has changed a little. The same is true for the literal sharing of this idea with others. With each articulation, I’ve added a new flourish or absorbed a bit of my listener’s or reader’s reaction. Sometimes it gets better; sometimes worse. It may evolve or it may fizzle out. With any luck, there’s still an expression of that initial spark and a roadmap for seeing how far it’s come. But that doesn’t need to happen. And that’s okay.

There is no one way to find inspiration, or to write what comes next. To nurture these ideas, writers might do best to follow their animal instincts.

Below are a few writers discussing their own inspiration and what comes after. They are taken from the second volume of The Paris Review’s The Writer’s Chapbook (excerpts from their interviews) that I’ve been reading recently.

“I don’t understand the process of imagination—though I know that I am very much at its mercy. I feel that these ideas are floating around in the air and they pick me to settle upon. The ideas come to me; I don’t produce them at will. They come to me in the course of a sort of controlled daydream, a directed reverie.”—Joseph Heller

“I think the first impulse comes from some deep emotion. It may be anger, it may be some sort of excitement. I recognize in the real world around me something that triggers such an emotion, and then the emotion seems to cast up pictures in my mind that lead me towards a story.”—John Hersey

“Language is your medium. You can be talking or writing a letter, and out comes an observation, a ‘sentence-sound’ you rather like. It needn’t be your own. And it’s not going to make a poem, or even fit into one. But that twinge it gives you—and it’s this, I daresay, that distinguishes you from ‘the citizen’—reminds you you’ve got to be careful, that you’ve a condition that needs watching.”—James Merrill

“I have little pieces of writing that sit around collecting dust, or whatever they’re collecting. They are drawn to other bits of narrative like iron filings. I hate looking for something to write about.”—Louise Erdrich

“Watching, listening, remembering. A lot of them from my friends or people I meet. Sometimes from a general feeling or belief which is strong enough to make me invent characters and situations to state it.”—Irwin Shaw

-2018 WROB Fellow Gabriella Gage

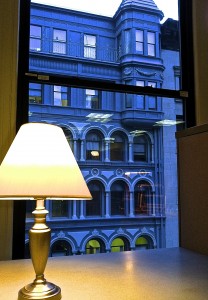

On a brief personal a note, this is my last blog post as a Fellow at the Writers’ Room. I was shocked when Debka emailed me a year ago with the news: you’ve been chosen, she wrote. The Room would like to offer you a Fellowship. It was a privilege to have been given the time to work and to think of myself solely as a ‘writer.’ I’m grateful. I offer thanks to the Board and to all the other members. I’m excited to stay on at the Room, and to continue writing and sharing my work in this vibrant community. For the foreseeable future I’ll still be writing at my favorite desk near the State Street window, and I’ll still have my hammer and nails at the ready. Please let me know what needs fixing.

On a brief personal a note, this is my last blog post as a Fellow at the Writers’ Room. I was shocked when Debka emailed me a year ago with the news: you’ve been chosen, she wrote. The Room would like to offer you a Fellowship. It was a privilege to have been given the time to work and to think of myself solely as a ‘writer.’ I’m grateful. I offer thanks to the Board and to all the other members. I’m excited to stay on at the Room, and to continue writing and sharing my work in this vibrant community. For the foreseeable future I’ll still be writing at my favorite desk near the State Street window, and I’ll still have my hammer and nails at the ready. Please let me know what needs fixing.